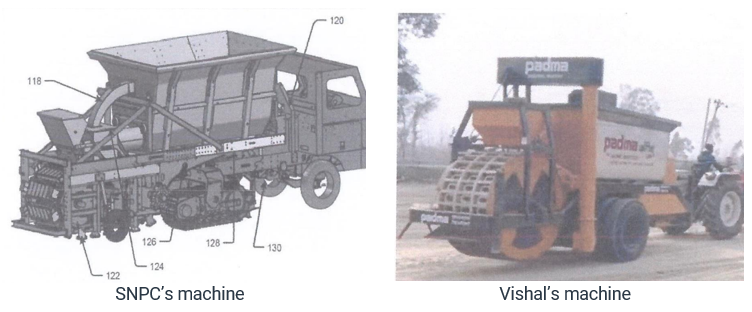

The overarching issue in SNPC Machines Private Limited & Ors. v. Mr. Vishal Choudhary revolves around the application of the doctrine of equivalents to determine patent infringement, focusing on whether functional similarities between two competing brick-making machines constitute a violation of patent rights, despite differences in their physical designs and mechanisms.

In April 2024, the plaintiff, SNPC Machines Private Limited & Ors. (SNPC), filed an infringement suit related to brick-making machines against defendant, Vishal Choudhary (Vishal Choudhary), sold under name of Padma Brick Making Machine in the Delhi High Court. The suit sought “permanent injunction” restraining Vishal from using, making, manufacturing, offering for sale or selling or importing impugned brick-making machines.

The suit patent in question is SNPC’s mobile brick-making machine that molds and lays bricks as it moves, controlled by an operator from a cabin. SNPC claimed that Vishal’s machine is doing the same work, in almost the same manner to accomplish the same results as SNPC’s brick-making machine.

However, Vishal contented that there were distinct differences between the two – Vishal’s machine lacked a cabin and steering mechanism, was designed to be towed by a tractor instead of an integrated mobility system like SNPC’s machine and utilized kinetic energy for operation, in contrast to the electrical energy powering SNPC’s machine.

Vishal argued that since their machine did not include every element specified in the patent claims, they did not infringe on the suit patent, invoking the ‘all elements rule’ as a defense. Furthermore, they raised the issue of prosecution history estoppel, stating that SNPC has previously focused only on roller and die assembly matters, which helps in shaping and forming the bricks, whereas now it was also emphasizing the machine’s integrated mobility.

SNPC countered stating that such differences were “trifling and insignificant” and that Vishal’s machine performed absolutely no function while it was stationery, and therefore included wheels to ensure mobility. They invoked ‘the pith and marrow of the invention’ principle and urged the Delhi High Court to not focus only on the “literal infringement”. Furthermore, they urged the Court to apply the “Doctrine of Equivalents”, to check whether the substituted element in the infringing product does “the same function” in substantially “the same way” to accomplish substantially “the same result” (triple identity test). In other words, SNPC claimed that Vishal had merely replaced the integrated mobility of SNPC’s machine with the tractor, to achieve exactly the same result.

The Court concurred with SNPC that the Doctrine of Equivalents should be applied, using the triple identity test, to determine if Vishal’s machine performs the same function in the same way to achieve the same result as SNPC’s product. The doctrine suggests that an invention can infringe on a patented invention if it functions almost the same way and produces a similar result as the patented invention, even if there may be minor differences between the elements or features of the two products. In other words, if the infringing product is equivalent to the patented invention in terms of its functionality, it may still be considered infringing.

Further the Court noted that while there were differences between SNPC and Vishal’s machine, these differences did not detract from the fundamental aspect of the invention – i.e., the mobility to ensure mobility of the assembly, albeit through different mechanisms. The Court concluded that these differences, according to the doctrine of “the pith and marrow”, were integral to the core functionality of the invention. The Court further interpreted that, without “mobility” the Vishal’s machine would serve no purpose considering it had a roller and die mechanism as well, therefore did not absolve them of infringement.

The Court considering all the facts and evidence, submitted granted a interim injunction in favor of SNPC, restraining Vishal from manufacturing and selling brick-making machines similar to the Plaintiffs’ patented brick-making machines. By focusing on the essential functionality of the patented invention, the Court helped protect SNPC against infringement, promoting innovation and fair competition in the market.

This judgment highlights the importance of the doctrine of equivalence in patent infringement cases, where there are two similar products and the question is whether one product performs the same function in the same way to achieve the same result as the patented invention, despite minor differences in their elements.