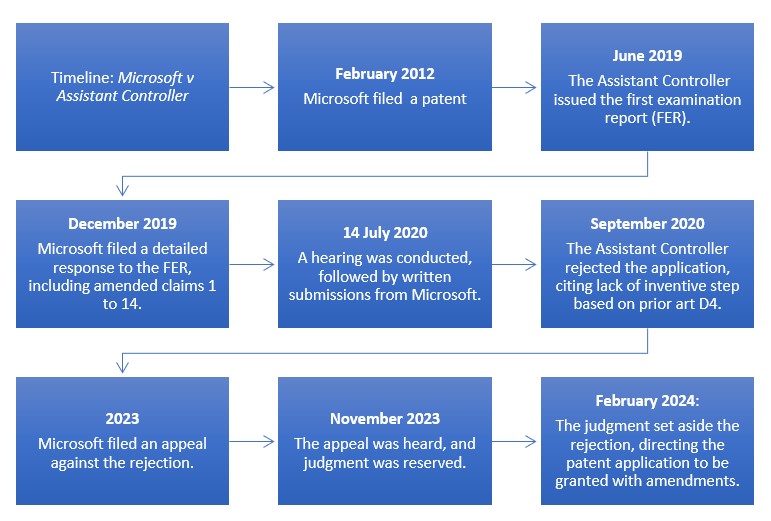

In the case of Microsoft Technology Licensing LLC v Assistant Controller of Patents and Designs, an appeal filed by Microsoft Technology Licensing LLC (Microsoft) challenged the rejection of its patent application for a system to improve how devices handle and communicate sensor data more efficiently in the Madras High Court.

The impugned order by the Assistant Controller of Patents and Designs (Controller) refused the application on the grounds of “lack of inventive step” under section 2 (1)(ja) of the Indian Patents Act, 1970 largely on the basis that the claimed invention was nearly identical to the prior art cited. Furthermore, it was also obvious to the Person Skilled in The Art (PSITA) based on the teachings of cited prior art document. In other words, it was contended that disclosures in the cited prior art document enabled a PSITA to arrive at the claimed invention in Microsoft’s patent application. Dissatisfied with the Controller’s decision, Microsoft appealed before the Intellectual Property Division (IPD) of the Madras High Court.

Microsoft contended that:

- The Controller, while examining Microsoft’s patent application, did not take the well-established three-step analysis, i.e., the invention disclosed in the prior art; the invention disclosed in the application under consideration; and the manner in which the subject invention would be obvious to a PSITA. Thus, the Controller had violated the Principles of Natural Justice which entails making a sensible and reasonable decision-making procedure on a particular issue;

- The Controller recorded a vague statement that a PSITA is assumed to be willing to make trial-and-error experiments to get it to work.

- The Controller failed to consider the technical problem, and the technical solution provided by the claimed invention in relation thereto.

- The Controller thus wrongfully refused Microsoft’s patent application on the grounds of “lack of inventive step” without considering Microsoft’s arguments.

Based on Microsoft’s contention, the Court analyzed the impugned order and observed that the Controller had indeed examined Microsoft’s patent application without ascertaining whether the cited prior document contains any teaching or suggestion that motivates or enables the PSITA to arrive at the claimed invention in the Microsoft’s patent application.

A technical problem was identified in the field of sensor data communication when an application programming interface (API) allows software applications to read sensor data through sensor interfaces. Such sensor interfaces complicate the design of the entire software because they typically involve complex control flow loops that respond to events. Due to the complexity of using sensor data through a typical sensor interface, many programs/software applications do not make use of sensor data.

This technical problem was addressed by the claimed invention in the Microsoft patent application by providing sensor readings in the form of lightweight messages to multiple applications running on a computer device, and thus reduces the complexity in communication of the sensor data.

The Court observed that both the claimed invention and the cited prior art deal with transmission of sensor data to a subscribing application. In the cited prior art, the transmission is triggered by an event of interest. The claimed invention indicates that a sensor service is used in the claimed invention, whereas such sensor service is not a part of cited prior art.

The other aspect to notice is that the claimed invention enables the subscribing application to receive and process messages rather than to read raw sensor values. The cited prior art also provides for the subscription of sensor data and the publication thereof upon occurrence of an event of interest, but even disregarding the difference in terminology there is no indication therein that the ‘published data’ is in an easy-to-read form. The inference that flows from the above discussion is that the solution provided by the claimed invention is the conversion of raw sensor data into messages that are transmitted to the subscribing application and may be easily read by such application. By contrast, the cited prior art does not envisage the conversion of raw sensor data into easy-to-read messages.

Thus, the Court ruled that Microsoft is correct in stating that both the cited prior art and the claimed invention provide for the transmission of sensor data to a subscribing application, but the difference lies in the way such data is transmitted. This leads to the question of whether the difference or delta between the cited prior art and the claimed invention would be obvious to a person skilled in the art.

The Court answered this question by finding that the cited prior art does not address the problem of addressing the complexity in the communication of data from sensors to subscribing applications as addressed by the claimed invention. Further, the Court also viewed that the cited prior art neither suggests nor motivates the PSITA to arrive at the claimed invention solving the complexity in data communication.

Thus, referring to Section 2 (1)(ja) of the Act which defines “invention”, the Court reaffirmed that the assessment of inventive step of a claimed invention is to be made by a two-step process. The first one is the identification of feature(s), if any, that involves technical advancement over prior knowledge or having economic significance or both, and the second one is the determination of whether the technical advancement or economic significance or both of said feature(s) makes the invention non-obvious to a PSITA.

Taking this forward, the Court ruled that the Act underscores the centrality of the PSITA while evaluating inventive step. Thus, the obvious starting point is identifying the PSITA in the field of invention. By referring to Rhodia Operations v Assistant Controller of Patents & Designs, the Court clarified that the level of skill of the PSITA should be above average/good and that she/he should possess a skill set to do the job well. The Court further clarified that PSITA need not be omniscient, and that ingenuity or inventiveness cannot be attributed to her/him since the object of the exercise is to determine whether the claimed invention contains an inventive step.

Further, the Court ruled that to ascertain whether prior art contains teaching, suggestion or motivation to lead the PSITA to the claimed invention, it is important to closely examine the problem that the prior art document sets out to solve.

Thus, by closely examining the problem-solution approach set out in the cited prior art document and Microsoft’s patent application, the Court observed that despite similarities in functionality, the cited prior art document lacked explicit teachings or enabling disclosures regarding the inventive feature(s). This crucial disparity indicated that Microsoft’s patent application addressed a unique problem not addressed by the prior art.

In conclusion, the Court suggested minor amendments to independent claims to add clarity to inventive features, thereby setting aside the impugned order. The Court directed the Controller to grant the application subject to the suggested amendments in the independent claims of Microsoft’s patent application.

By emphasizing the significance of enabling teaching within the prior art as a determinant of patent validity, the judgement clarifies that the law requires prior art to sufficiently teach or enable a PSITA to create the claimed invention. Mere disclosure of similar functionalities or elements is insufficient if it does not provide explicit guidance or enablement for implementing the claimed invention.